Ever wondered what a Supreme Court judgment says, but did not have the courage to read through one?

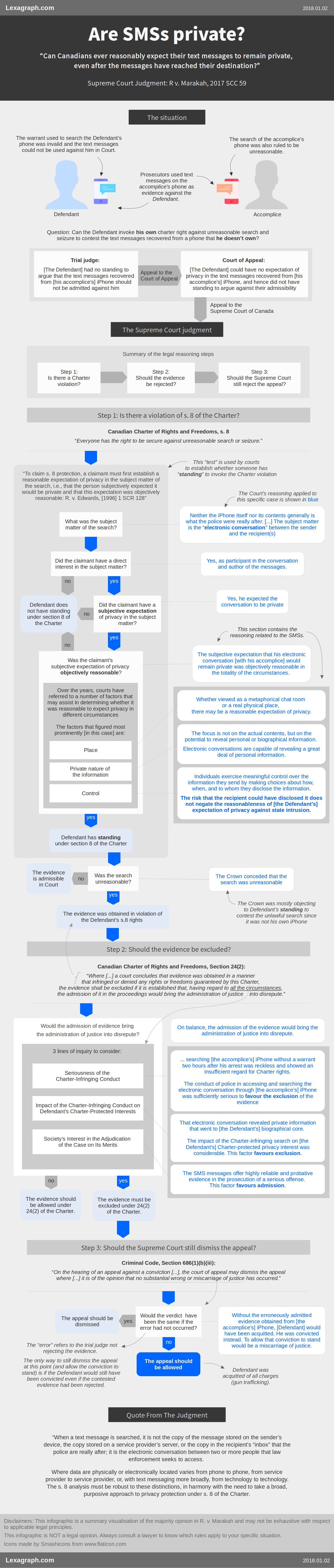

Well you’re in luck, because I’ve diagrammed a recent Supreme Court of Canada judgment which determined whether Canadians had a reasonable expectation of privacy over SMSs that have reached the recipient’s phone.

In this case, police arrested two suspects and illegally searched their phones. This meant the evidence from each phone couldn’t be used against the phones’ owners. At trial, the prosecutor used, against one of the suspects, the copy of the SMSs recovered from the accomplice’s phone, arguing that the suspect couldn’t contest the illegal search of someone else’s phone. The case was appealed all the way up to the Supreme Court.

Some notes, if you’re not a lawyer:

Civil rights are all about limiting State interference in people’s lives. The Supreme Court often defines civil rights principles in the context of a criminal case, as it is the most common situation where people and the State collide. As such, civil rights are often decided on cases where the defendants are not the most sympathetic ones and it is possible that criminals will be set free.

Cases that reach the Supreme Court are often very complex. Even when the question is not that complex, the ultimate ruling often depends on a chain of arguments, where any link in the chain may break the whole case. In the case below, for example, from a technical point of view, the actual ruling on privacy of SMSs is an accessory to the bigger question of whether a piece of evidence is admissible in court. Yet the reason this case went all the way up to the Supreme Court is exactly on this specific point.

If you do read the full judgment, which I recommend you do (the majority ruling is only 82 of the 200 paragraphs), you’ll notice that the Supreme Court does not take civil rights lightly. On the contrary, it adopts a point of view that tends towards broadening, rather than restricting, privacy rights. The following quote illustrates this point of view:

To accept the risk that a co-conversationalist could disclose an electronic conversation is not to accept the risk of a different order that the state will intrude upon an electronic conversation absent such disclosure. “[T]he regulation of electronic surveillance protects us from a risk of a different order, i.e., not the risk that someone will repeat our words but the much more insidious danger inherent in allowing the state, in its unfettered discretion, to record and transmit our words”: Duarte, at p. 44.

Hello,

I love the work you are going to make law more accessible. Keep up the good work.